Electric vehicles have been around far longer than you might think. While today’s EV market is dominated by futuristic cars like Tesla, electric vehicles first made their debut well before gasoline engines became the norm.

In fact, the first electric cars were hitting the streets in the early 19th century—yes, we’re talking about a time when horse-drawn carriages were still in full swing. But before we get to why EVs faded into the background for decades, let’s start at the beginning.

Early Beginnings: The First Electric Vehicles (1830s–1850s)

The electric vehicle story kicks off in Scotland in the 1830s. Robert Anderson, a Scottish inventor, was tinkering with motorized carriages as early as 1832, and while he built one of the first electric-powered carriages, it wasn’t exactly practical.

Anderson’s invention ran on non-rechargeable batteries, which limited its usefulness—you couldn’t just plug it in and go, so it was more like a fancy toy than a solution for transportation.

Meanwhile, Robert Davidson—also from Scotland—took a different approach. In 1837, he built an electric locomotive that ran on batteries. By 1841, Davidson had created a larger version that could pull six tons for 1.5 miles at a blistering speed of 4 mph.

While this might not sound impressive now, at the time, it caused quite a stir, especially among railway workers who felt their jobs were on the line. Davidson’s invention was sabotaged, setting a curious tone for the future of EVs—innovation was always in a fight with tradition.

But the true game changer came in 1859 when French physicist Gaston Planté invented the rechargeable lead-acid battery. Planté’s breakthrough meant that electric vehicles could recharge instead of requiring a new battery every trip, marking the beginning of EVs as we know them today.

It didn’t mean electric vehicles were instantly practical, but it certainly opened up new possibilities.

A New Era: The 1880s and 1890s

Fast forward a few decades, and EVs started to move from novelty to practicality. Thomas Parker, an English inventor, was already making waves with his electric trams and public transportation systems in the 1880s. He saw the potential for electric propulsion in cars and built prototype electric vehicles.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, William Morrison, a Scottish-born chemist living in Iowa, was working on something similar. Morrison developed an electric carriage that could reach speeds of 20 mph and had a range of about 50 miles on a single charge—a major leap forward at the time.

Morrison’s electric vehicle was showcased at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where it became a sensation. People weren’t just impressed by its quiet, clean operation, but also by its potential to revolutionize personal transportation.

Up until then, transportation had been dominated by horse-drawn carriages, and for the first time, electric cars gave city-dwellers a glimpse of the future.

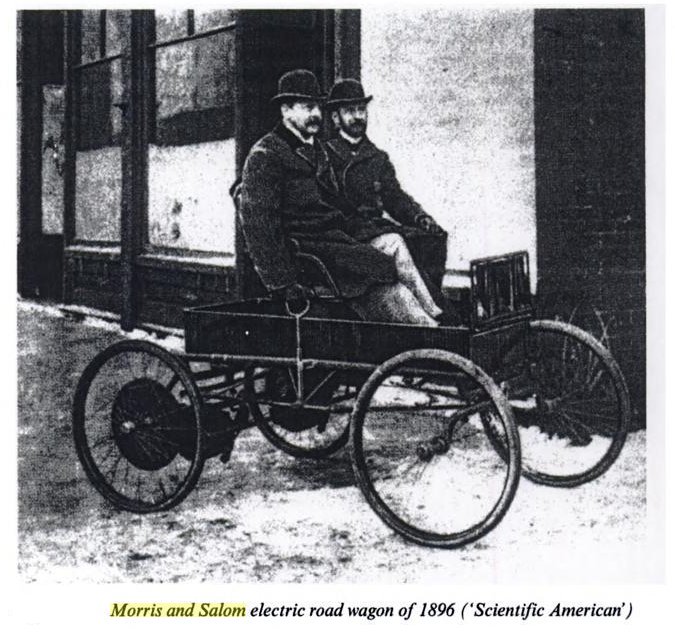

Around the same time, two entrepreneurs from Philadelphia—Pedro Salom and Henry G. Morris—took electric vehicles even further. In 1894, they developed the Electrobat, the first commercially viable electric vehicle.

The early versions were slow and heavy, but by 1896, they had refined the design into a faster, lighter vehicle that could travel up to 20 mph and had a range of around 25 miles. This was no longer just a science experiment—electric vehicles were on the road, and they were here to stay, or so it seemed.

Early Success: Electric Taxis and Battery Swapping (Late 1890s–1900s)

Salom and Morris weren’t content with just making personal EVs; they saw an opportunity in commercial transportation. They founded the Electric Vehicle Company (EVC), which became famous for rolling out over 600 electric taxis in New York City by the early 1900s.

At the time, gasoline cars weren’t even a real competitor yet, and EVs dominated urban areas.

EVC also pioneered a battery-swapping station—a concept that’s surprisingly similar to some of today’s most innovative EV infrastructure. Drivers could pull in, swap out their drained battery for a fully charged one, and get back on the road in minutes.

It was a brilliant solution to one of EVs’ biggest limitations: long recharge times. Unfortunately, the company expanded too quickly, faced internal conflicts, and collapsed by 1907.

The Rise of Gasoline: The Early 1900s

By the early 1900s, electric vehicles were riding high. They were quiet, easy to drive, and perfect for urban transportation. So what went wrong? Enter the gasoline engine. While EVs had captured early success, gasoline-powered vehicles were lurking in the wings, ready to take over.

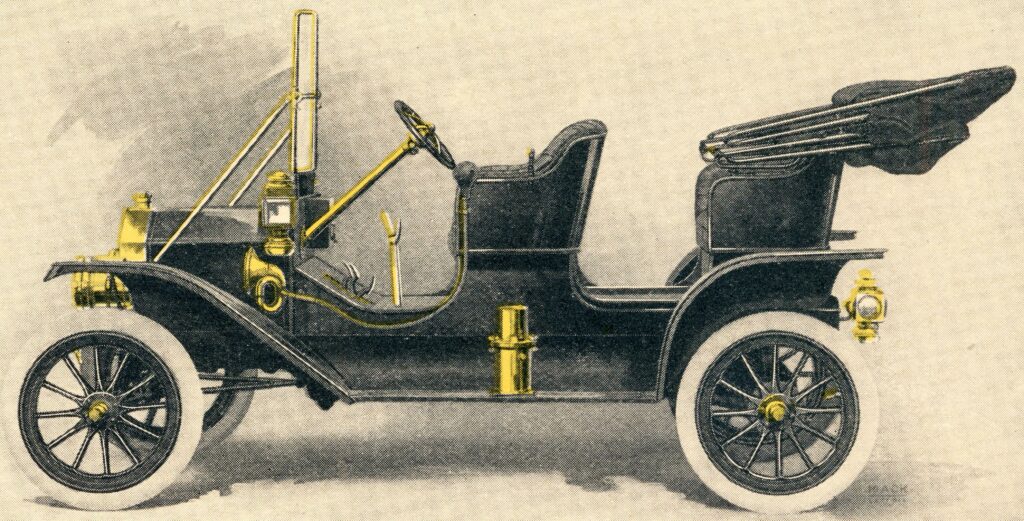

The big turning point came in 1908, when Henry Ford introduced the Model T, a gasoline-powered car that was affordable, fast, and reliable. The Model T started at $850 (and later dropped to as low as $300), making it accessible to the average consumer—something electric vehicles couldn’t match.

Suddenly, gasoline-powered cars became the more practical choice for long-distance travel and affordability.

Not only were gasoline cars cheaper, but the infrastructure supporting them exploded. Gas stations began popping up across the U.S., making refueling quick and easy, even in rural areas. In contrast, electric cars were still limited to urban environments where electricity was readily available.

As if that wasn’t enough, in 1912, Charles Kettering invented the electric starter for gasoline engines, eliminating the need for hand-cranking. One of the few advantages electric vehicles had over gasoline cars—ease of use—was gone.

With the advent of the electric starter, gasoline cars became just as easy to operate as electric vehicles, if not easier.

World War I and the Decline of Early EVs

Even though gasoline-powered cars were rising, electric vehicles still managed to hang on for a bit longer, especially in urban settings. Companies like Detroit Electric continued producing electric cars for wealthy city dwellers who appreciated their quiet operation.

In fact, Clara Ford, Henry Ford’s wife, famously preferred her Detroit Electric to her husband’s gasoline-powered cars. For a while, EVs remained the car of choice for the elite, who valued luxury over speed and range.

But after World War I, electric vehicles couldn’t keep up with the rapidly improving gasoline cars. With cheap gasoline, new roads connecting cities, and a booming oil industry, electric vehicles became increasingly obsolete. By the 1920s, the writing was on the wall—EVs were fading fast.

The Dark Ages of Electric Vehicles (1930s–1970s)

The period between the 1930s and 1970s is often referred to as the “dark ages” of electric vehicles. Gasoline-powered cars were dominating, and electric vehicles were relegated to niche markets, such as milk floats in the UK and warehouse trucks in industrial settings.

Lead-acid batteries still had severe limitations, offering poor range and long charging times, which made EVs impractical for mainstream use.

Automakers weren’t interested in developing EVs because consumer demand was non-existent. Gasoline was cheap, and the infrastructure supporting internal combustion engines continued to grow. The oil industry was booming, and as long as gasoline was affordable, there wasn’t much incentive to switch to electric power.

That all changed when the 1970s oil crisis hit, causing gasoline prices to skyrocket and making people question their dependence on oil.

Governments began to push for alternative fuel sources, and automakers—slowly—started revisiting the idea of electric vehicles. But even then, it would take decades before electric cars returned to the mainstream.

Electric Cars in Motorsports: A Speed Revolution

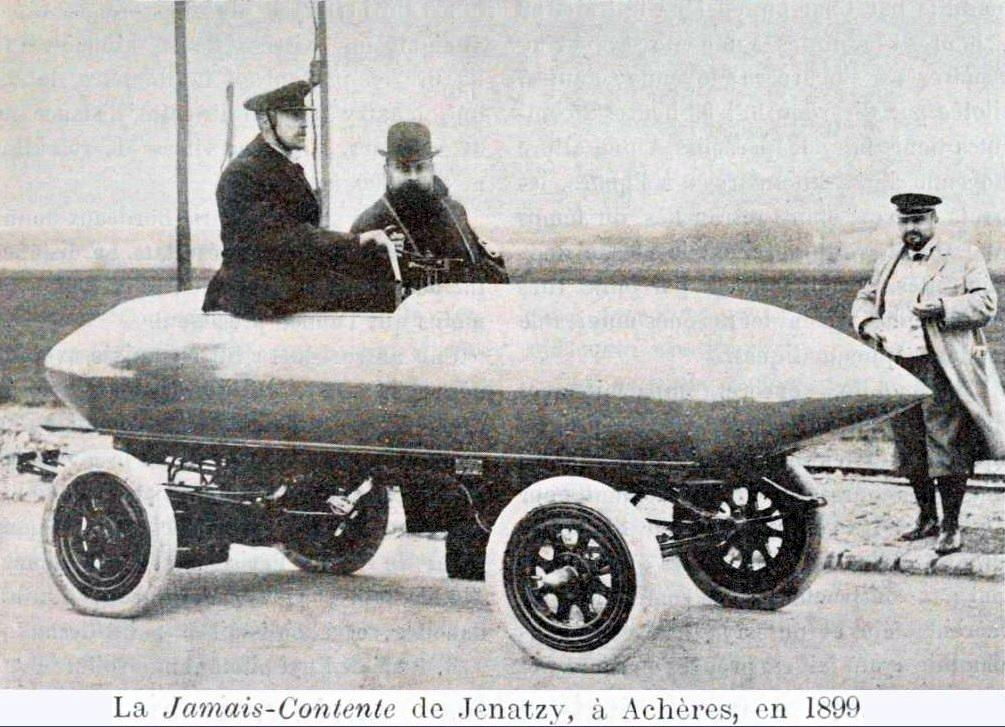

Despite the rise of gasoline cars, electric vehicles made significant strides in motorsports. The most notable was Camille Jenatzy, who, in 1899, set the first world speed record in an EV.

His torpedo-shaped car, La Jamais Contente, hit 100 km/h (60 mph), proving that electric vehicles weren’t just slow, practical machines—they could be fast, too. Jenatzy’s success showed that electric cars had real potential, even in an industry that soon became dominated by gasoline engines.

The End of the First Era of EVs

By the 1930s, the first era of electric vehicles had come to an end. Companies like Detroit Electric and Baker Electric continued producing cars for niche markets, but they were the exceptions, not the rule. In 1939, the last Detroit Electric vehicle rolled off the production line, marking the end of an era.

While electric vehicles largely disappeared from the consumer market, they weren’t forgotten. EVs remained in specialized roles, such as delivery vehicles, and their legacy persisted in the minds of engineers and innovators. As concerns about gasoline dependence grew, so did interest in electric alternatives—setting the stage for the eventual EV revival.